Margaret Begbie

National Fire Service

Tadeusz Brylak

Polish Army

James Drysdale,

Gunner, Royal Artillery

Jim Wylie - Bevin Boy

Born – Paisley, 1926

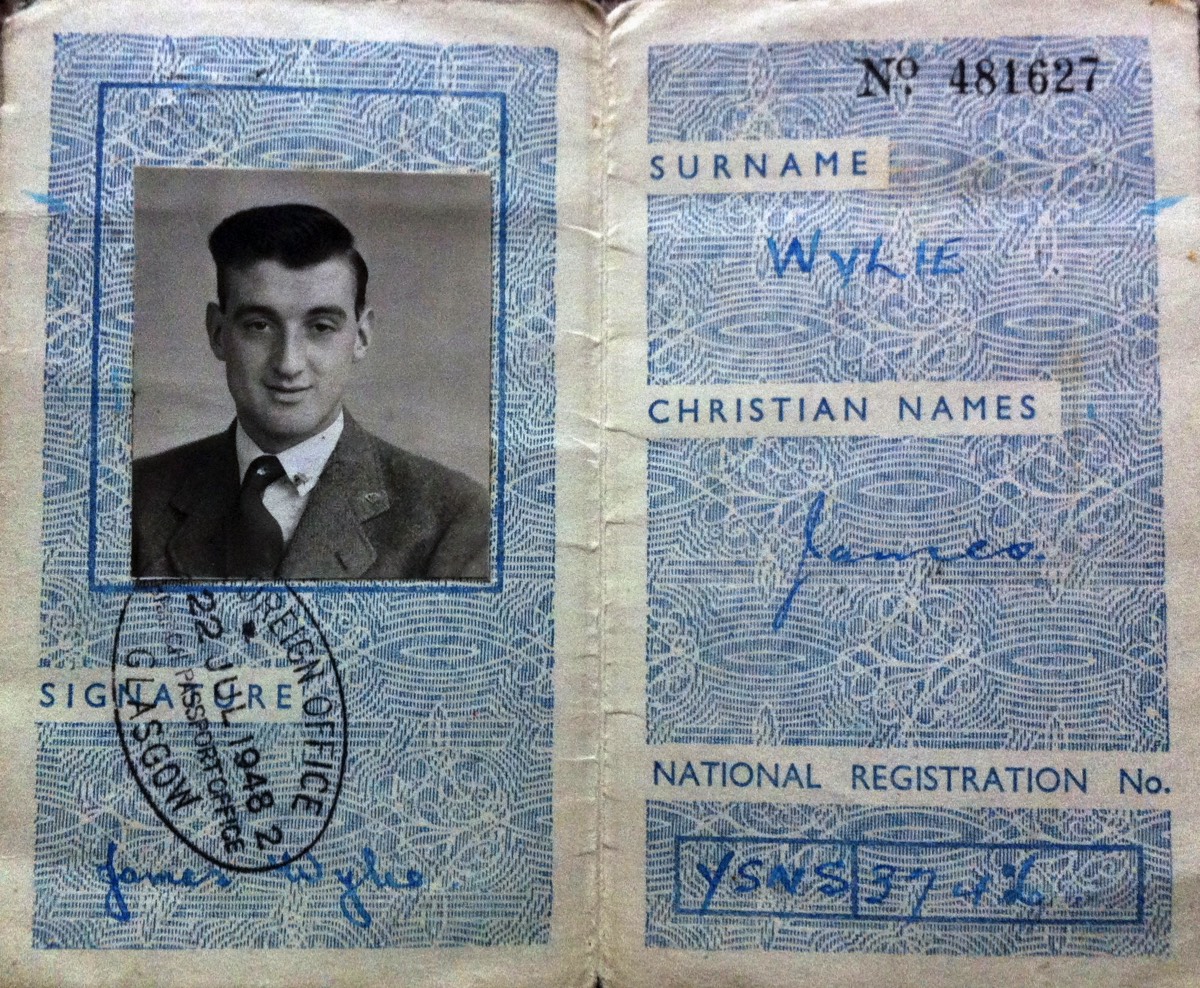

Jim Wylie’s travel ID, 1948.

Jim Wylie, Haddington, 2013.

The first time Jim was away from home was when he went to the mines. He got his call up papers after the Christmas holidays. ‘It was a war miners fought every day but for me it was a strange world, one which was very painful physically.’ When he was sent to the Townhill Training camp he was first told to dig a hole in the morning and fill it in in the afternoon. “This was to harden us up ready to face the rigours of mining and I remember very distinctly when I first put on pit boots with steel toecaps and I remember skiing down the hill in Townhill. I’d never worn boots before’. He was eighteen when he went into the mines and stayed in a billet in Cowdenbeath. All the (Bevin Boy) miners in Scotland were brought down to train in Dunfermline and live in Cowdenbeath and were then sent out to mines all over Scotland. Jim was sent to the ‘Nelly’ coal mine (Lochgelly).

How did you feel when you were conscripted into the mines?

‘Well, I did volunteer for the navy but unfortunately I didn’t get into it. I didn’t have any desire to join the army, so I chose the mines. Whether that was a good thing or not you can judge later on.’

You were conscripted but you still had a choice?

‘Yes, not which service I went into (because I tried for the navy), but I still had a choice.

When I got there (Lochgelly) my experience in the mine was quite dramatic in a sense, for this was a different world for me, a strange world. I can remember going down the mine for the first time. It was the habit that the engineman who took the cage down would let the lever go when he knew there were Bevin Boys going down and the cage used to rattle down and the water and the shuggling, oh, it was frightening and your head was down by your feet. It was quite an experience.

That was going down the mine, but we had a lot of work on the surface. This was an experience for me too because as a piano tuner, while I was fit enough, I had many deficiencies as a miner because when you were on the surface you had to unload a thirteen ton wagon of sand and when you see a thirteen ton wagon to be moved by shovel it's a big job. Often in the wintertime we used to have six feet lengths of Scots Pine to heave out of a wagon over the edge onto the railway. This was another arduous and unpleasant job but possibly the worst job was to unload a thirteen-ton wagon of common bricks: your hands were torn to bits. This was something the miners did every day, but it was very hard for us. But the miners were very appreciative of the Bevin Boys.’

So, relations were quite good between you and the miners?

‘Oh yes, very much so. I think the miners made quite a play of the Bevin Boy’s inability to catch up with the physical side of mining and we got a lot of hard hassle for that, but they were very helpful and helped us cope with life as a miner.

The very first time I went down a mine I realised that the everyday experiences of the miners was very different to those the Bevin Boys faced. I was sitting at the Road end, where I was told to sit for the miners who might ask for some wood or whatever, and I sat there the first time and suddenly there was a dull explosion and the earth started rattling on my hat. The suddenness of the impact of the shot firer putting down the coal was quite frightening at first. You soon became aware of your environment. You pushed to the back of your mind that anything could happen here at any time.

As an example, I used to work on the face on a machine which took the coal down onto the main haulage belt, a drop of three or four feet. The belt was too short to reach the face and u-shaped metal pans shuggled the coal along from the face to the belt. The noise of these plates and the dust made me realise that, as a piano tuner, I was in an environment I shouldn’t be in. Eventually it did affect my hearing. I had formerly gone to concerts in Glasgow and I remember, as all this screeching was going on, trying to remember a Beethoven symphony to get my mind away from the noise.

On that particular section the system at the coal face was that it was split into three sections, the coal was solid and then there was a place where you worked and then the next sub-section was waste. The waste was allowed to break where they had pillars of beech blocks that supported it. The earth was allowed to fall down and the whole section was moved on and the area where the coal was was now a working area. This system moved all the time. The waste section was used as a toilet and I remember one occasion this particular seam had no support on the roof and had sections working up above which meant that the strata was all broken up and had to be supported by wooden battens and corrugated 6” straps all along.There was a fall and the whole far end of the section just came clattering down onto the pans. Fortunately, no one was hurt that time but the consternation when the belt and the pans stopped working! It was essential that the coal was taken out and every means was put to the task of getting the coal working again. That was a bit hairy because I was pushed into this void above me and told to push things back, so I was glad to get out of that situation.’

Bevin Boys don’t tend to get as much recognition after the war as those who fought with the armed forces. How do you feel about that?

‘Very strongly. When we watched a memorial service in London the guys with all the medals always impressed me and we learnt about all the various actions they’d been in. I admired them greatly but there was an even greater sense of pride when you saw the men with the white helmets [i.e. miners]. I don’t think people realise the difficulties these young guys faced when they went into the mines and had to cope with a very unpleasant environment every day. Of course, this applied to the miners too, but that was the life which the miners had chosen. It wasn’t one we chose. Many of the Bevin Boys are now gone and I always wish I had the courage to wear my white hat because, of course, we’re not recognised, we don’t have any badge of honour. If I got in touch with other Bevin Boys, I might have the courage to get that white hat on again.’

How did you feel when you were conscripted into the mines?

‘Well, I did volunteer for the navy but unfortunately I didn’t get into it. I didn’t have any desire to join the army, so I chose the mines. Whether that was a good thing or not you can judge later on.’

You were conscripted but you still had a choice?

‘Yes, not which service I went into (because I tried for the navy), but I still had a choice.

When I got there (Lochgelly) my experience in the mine was quite dramatic in a sense, for this was a different world for me, a strange world. I can remember going down the mine for the first time. It was the habit that the engineman who took the cage down would let the lever go when he knew there were Bevin Boys going down and the cage used to rattle down and the water and the shuggling, oh, it was frightening and your head was down by your feet. It was quite an experience.

That was going down the mine, but we had a lot of work on the surface. This was an experience for me too because as a piano tuner, while I was fit enough, I had many deficiencies as a miner because when you were on the surface you had to unload a thirteen ton wagon of sand and when you see a thirteen ton wagon to be moved by shovel it's a big job. Often in the wintertime we used to have six feet lengths of Scots Pine to heave out of a wagon over the edge onto the railway. This was another arduous and unpleasant job but possibly the worst job was to unload a thirteen-ton wagon of common bricks: your hands were torn to bits. This was something the miners did every day, but it was very hard for us. But the miners were very appreciative of the Bevin Boys.’

So, relations were quite good between you and the miners?

‘Oh yes, very much so. I think the miners made quite a play of the Bevin Boy’s inability to catch up with the physical side of mining and we got a lot of hard hassle for that, but they were very helpful and helped us cope with life as a miner.

The very first time I went down a mine I realised that the everyday experiences of the miners was very different to those the Bevin Boys faced. I was sitting at the Road end, where I was told to sit for the miners who might ask for some wood or whatever, and I sat there the first time and suddenly there was a dull explosion and the earth started rattling on my hat. The suddenness of the impact of the shot firer putting down the coal was quite frightening at first. You soon became aware of your environment. You pushed to the back of your mind that anything could happen here at any time.

As an example, I used to work on the face on a machine which took the coal down onto the main haulage belt, a drop of three or four feet. The belt was too short to reach the face and u-shaped metal pans shuggled the coal along from the face to the belt. The noise of these plates and the dust made me realise that, as a piano tuner, I was in an environment I shouldn’t be in. Eventually it did affect my hearing. I had formerly gone to concerts in Glasgow and I remember, as all this screeching was going on, trying to remember a Beethoven symphony to get my mind away from the noise.

On that particular section the system at the coal face was that it was split into three sections, the coal was solid and then there was a place where you worked and then the next sub-section was waste. The waste was allowed to break where they had pillars of beech blocks that supported it. The earth was allowed to fall down and the whole section was moved on and the area where the coal was was now a working area. This system moved all the time. The waste section was used as a toilet and I remember one occasion this particular seam had no support on the roof and had sections working up above which meant that the strata was all broken up and had to be supported by wooden battens and corrugated 6” straps all along.There was a fall and the whole far end of the section just came clattering down onto the pans. Fortunately, no one was hurt that time but the consternation when the belt and the pans stopped working! It was essential that the coal was taken out and every means was put to the task of getting the coal working again. That was a bit hairy because I was pushed into this void above me and told to push things back, so I was glad to get out of that situation.’

Bevin Boys don’t tend to get as much recognition after the war as those who fought with the armed forces. How do you feel about that?

‘Very strongly. When we watched a memorial service in London the guys with all the medals always impressed me and we learnt about all the various actions they’d been in. I admired them greatly but there was an even greater sense of pride when you saw the men with the white helmets [i.e. miners]. I don’t think people realise the difficulties these young guys faced when they went into the mines and had to cope with a very unpleasant environment every day. Of course, this applied to the miners too, but that was the life which the miners had chosen. It wasn’t one we chose. Many of the Bevin Boys are now gone and I always wish I had the courage to wear my white hat because, of course, we’re not recognised, we don’t have any badge of honour. If I got in touch with other Bevin Boys, I might have the courage to get that white hat on again.’

Jim’s Bevin Boy medal [It says ‘Veteran’ at the bottom].

How long did you work in the mines?

‘Three years, from 1942 to 45. I became a piano tuner and set up my own business after the war. This was a great disturbance like most things that happened in the war. Yes, it was a difficult time.’

Where did you work as a Bevin Boy?

‘I worked in the Nelly, in Lochgelly, and in Cowdenbeath, perhaps No 7, just off the main road. But I didn’t work there very long fortunately because that wasn’t a very pleasant environment, very wet, compared to the Nelly which was drier.’

Do the Bevin Boys have an association?

‘Yes, they do and a website. Fatalities in the mines with the Bevin Boys wasn’t high though I remember one guy somewhere down south who was killed when a girder came down and hit him on the back of the neck. There were fatalities. The environment in the mines was just horrendous, lots of accidents, tubs coming down on wires and, of course, we didn’t help ourselves by going in conveyor belts along roads which weren’t well supported and seeing these fungus-covered timbers. It was quite an experience to see nature taking over. Scary!

I had one experience when I was using Carbide lamps, lamps filled with Carbide and water dripped onto it and produced a flame and my lamp went out and I’d no water, no means of getting about and there I was, stuck on this roadway with no light, no lights at all and then suddenly I saw a light coming round a bend and I thought thank goodness for that. Another moment that is impressed on me.

It was a changing industry and later on became mechanised. I was there during the nationalisation of the mines and I remember there was a great flurry of activity, generators, etc., being put on lorries to get away to sell before nationalisation. That was something I didn’t approve of.’

Do you have any happy memories of that time?

‘Yes, well, I think adversity brings its own pleasure. To be part of the mining community and, while not of them, you were there with them. Yes, while conditions were extremely bad, I didn’t have any grudge about the hard work or the danger I was in.’

Did the politics of the miners rub off on you at all?

‘Yes, the politics were very interesting. I was speaking about the engine man; he was a Communist and he used to sit and talk to me about what had happened during the General Strike when the miners used to run full wagons down a slope to destroy parts of the pit head. They were very aggrieved at the conditions and working in the conditions you could see the reason why they were aggrieved. Yes, I would say in some ways it has affected me because you can’t live in that environment without realising what they were fighting for.’

How did news of the war situation reach you? Did people talk about it all the time down the pit?

‘Not terribly much when I was down the mine because your very breath was taken with the shovel. You didn’t have time to talk about it but when we went back to the billet at the camp in Cowdenbeath some of us did talk about politics, though not to any great depth, and I was certainly aware of the war and all the things that were happening. Like everybody else we were concerned.’

So, you listened to the radio?

‘Oh yes. There wasn’t much talking about the war down the mine. We just talked about the pub and which one had good beer so that the coal dust could be washed down easy.’

What about entertainment?

‘We used to go to the dance in Kirkcaldy and some of the local hops. There was one occasion when I was at one of these and a wee lad tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Gie me a shot mister!”; so that was a cultural shock for me. And I remember going to the local cinema with a local girl and getting a kiss in the back row, so that was my introduction to women.

I had occasion to be in digs in Lochgelly, just at the bottom of the Rise, with Mr and Mrs Sinclair. He was a miner who did contract work. His job was to get a section and to get other miners to help him clear it. He was a robust and energetic man who used to go up front and shovel the whinstone, a terribly heavy stone, back and if you didn’t clear it you got buried. But the conditions in the cottage were just excellent and, of course, the miners were well supplied with coal for cooking and heating, though the cottage was also supplied with gas. They were real genuine people who treated us with real, genuine respect. Yes, they were part of the family.’

[Jim Wylie interviewed by D, Haire on Friday 13th December 2013]

‘Three years, from 1942 to 45. I became a piano tuner and set up my own business after the war. This was a great disturbance like most things that happened in the war. Yes, it was a difficult time.’

Where did you work as a Bevin Boy?

‘I worked in the Nelly, in Lochgelly, and in Cowdenbeath, perhaps No 7, just off the main road. But I didn’t work there very long fortunately because that wasn’t a very pleasant environment, very wet, compared to the Nelly which was drier.’

Do the Bevin Boys have an association?

‘Yes, they do and a website. Fatalities in the mines with the Bevin Boys wasn’t high though I remember one guy somewhere down south who was killed when a girder came down and hit him on the back of the neck. There were fatalities. The environment in the mines was just horrendous, lots of accidents, tubs coming down on wires and, of course, we didn’t help ourselves by going in conveyor belts along roads which weren’t well supported and seeing these fungus-covered timbers. It was quite an experience to see nature taking over. Scary!

I had one experience when I was using Carbide lamps, lamps filled with Carbide and water dripped onto it and produced a flame and my lamp went out and I’d no water, no means of getting about and there I was, stuck on this roadway with no light, no lights at all and then suddenly I saw a light coming round a bend and I thought thank goodness for that. Another moment that is impressed on me.

It was a changing industry and later on became mechanised. I was there during the nationalisation of the mines and I remember there was a great flurry of activity, generators, etc., being put on lorries to get away to sell before nationalisation. That was something I didn’t approve of.’

Do you have any happy memories of that time?

‘Yes, well, I think adversity brings its own pleasure. To be part of the mining community and, while not of them, you were there with them. Yes, while conditions were extremely bad, I didn’t have any grudge about the hard work or the danger I was in.’

Did the politics of the miners rub off on you at all?

‘Yes, the politics were very interesting. I was speaking about the engine man; he was a Communist and he used to sit and talk to me about what had happened during the General Strike when the miners used to run full wagons down a slope to destroy parts of the pit head. They were very aggrieved at the conditions and working in the conditions you could see the reason why they were aggrieved. Yes, I would say in some ways it has affected me because you can’t live in that environment without realising what they were fighting for.’

How did news of the war situation reach you? Did people talk about it all the time down the pit?

‘Not terribly much when I was down the mine because your very breath was taken with the shovel. You didn’t have time to talk about it but when we went back to the billet at the camp in Cowdenbeath some of us did talk about politics, though not to any great depth, and I was certainly aware of the war and all the things that were happening. Like everybody else we were concerned.’

So, you listened to the radio?

‘Oh yes. There wasn’t much talking about the war down the mine. We just talked about the pub and which one had good beer so that the coal dust could be washed down easy.’

What about entertainment?

‘We used to go to the dance in Kirkcaldy and some of the local hops. There was one occasion when I was at one of these and a wee lad tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Gie me a shot mister!”; so that was a cultural shock for me. And I remember going to the local cinema with a local girl and getting a kiss in the back row, so that was my introduction to women.

I had occasion to be in digs in Lochgelly, just at the bottom of the Rise, with Mr and Mrs Sinclair. He was a miner who did contract work. His job was to get a section and to get other miners to help him clear it. He was a robust and energetic man who used to go up front and shovel the whinstone, a terribly heavy stone, back and if you didn’t clear it you got buried. But the conditions in the cottage were just excellent and, of course, the miners were well supplied with coal for cooking and heating, though the cottage was also supplied with gas. They were real genuine people who treated us with real, genuine respect. Yes, they were part of the family.’

[Jim Wylie interviewed by D, Haire on Friday 13th December 2013]